In Conversation: What Does Reconciliation Really Mean to Canadian Businesses?

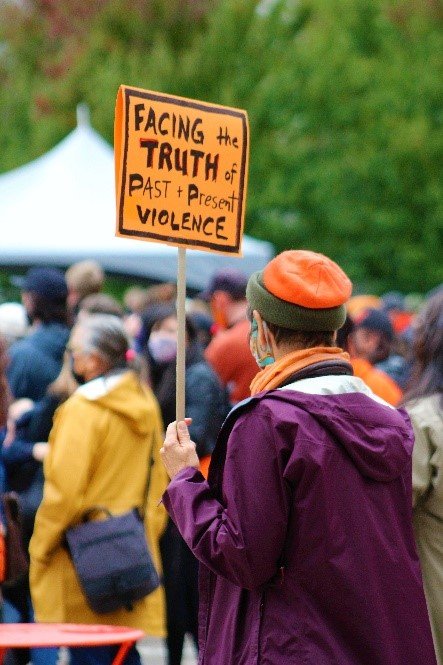

September 30th, 2022, marks Canada's 2nd National Day of Truth & Reconciliation. Although the Truth & Reconciliation Commission Report and Call to Actions were released in 2015, the government, the private & public sectors, and individuals have much more work to do to reconcile relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. To dig deeper into the meaning of reconciliation and understand how business organizations can meaningfully practice what they preach, we sat down with reconciliation experts and practitioners to hear what they have to say.

We thank these four trailblazers for their time and contribution to this important topic: Tanya Tourangeau, a proud Dene First Nation from the Northwest Territories and reconciliation consultant who focuses on bridging partnerships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous governments, organizations, and communities; Asma-na-hi Antoine from the Toquaht Nation of the Nuu-chah-nulth lands, a Director of Indigenous Engagement at Royal Roads University and is currently completing her PhD at Simon Fraser University; Joelle Walker, a legal advocate and experienced litigator (Lead + Principal of its Litigation Group at MillerTiterle +Company) having represented numerous communities in landmarking federal court appeal cases including the Trans Mountain Expansion Pipeline; and Zain Nayani, our Founder & CEO at ZN Advisory. Zain started his reconciliation journey by working with the T'eqt''aqtn'mux (Kanaka Bar Band) during his master’s at Simon Fraser University, which launched his passion for helping communities build organizational resilience.

1. What does reconciliation look like and mean to you (in the corporate world per TRC Call to Action #92)?

Tanya: My Vision of Truth and Reconciliation is represented within my consulting business’s Vision Statement: Through Reconciliation and Collaboration, Indigenous People and Canada thrive together. I want to see more thriving and less surviving amongst all of us, Indigenous people and non-Indigenous. We can accomplish that with win-win partnerships.

Zain: Reconciliation to me means going beyond the celebration of a couple of holidays in a year and wearing different colored shirts for different causes on different days. It is all very meaningful, and I get it, but reconciliation goes beyond that in my mind. It is an act of regular practice and our daily thought processes. To me, it means being an active part of the life of an Indigenous person or community on a regular basis. Not just on the statutory holidays! To me, it looks like mentoring young Indigenous people, living on and off-reserve, by establishing a personal connection with them. It also looks like staying in touch with community elders and participating in people’s life events such as birth and death. When I look at TRC CTA # 92 from a business-owner/corporate sector perspective, to me it looks like reaching out to, involving and getting free, prior and informed consent of local Indigenous communities on all business/development matters within their Territories; involving them in the workforce in an equitable and non-discriminatory way; and providing our own business’ workers with proper/relevant educational opportunities about the history of Indigenous peoples and colonization in Canada.

Joelle: Reconciliation in the corporate world begins with recognition that we have a responsibility to ensure our organization upholds the principles of UNDRIP not through words but through action. A commitment to the advancement of reconciliation should inform decisions we make on strategic and operational levels. Whether and how we have furthered this advancement must be meaningfully considered as a key performance indicator of our overall success as an organization. A reconciliation policy is a starting point, but only a starting point- the goal is robust and consistent application in all aspects of the business.

2. What is the biggest barrier you face in your work to implement reconciliation?

Tanya: Implementing reconciliation hasn’t been a barrier. I incorporate Indigenous Knowledge Systems influenced Change Management into the development process of creating reconciliation strategies, initiatives, and tasks so that employees, stakeholders, and partners are motivated and able to implement actions. Organizations that contact me are ready to start their journey of reconciliation. A barrier to reconciliation in Canada, in general, is understanding that we all deserve to be equal.

Joelle: The biggest hurdle for me as a litigator is to have the courts, industry, and government recognize that we are in a changing legal landscape that must adapt from a Western, colonial perspective of what the law is and how it is applied. Reconciliation, Indigenous legal orders and in BC, DRIPA, must be viewed as law that is to be incorporated into our legal system and robustly applied.

3. What has been your biggest success within your reconciliation work?

Tanya: Biggest successes occur in my work when Indigenous and non-Indigenous partners form meaningful relationships. When a Chief and a CEO, or equivalent, text each other, attend each other’s community events, and considers how decisions may affect all community members; that’s successful reconciliation in action! A partnership that exemplified that definition and beyond, was a partnership of 6: 2 First Nations, 2 townships, 1 county, and 1 community economic development corporation. Together, they overcame many challenges and disagreements to form a meaningful partnership that not only created a unique planning tool that honoured the traditional territory and provided a tool for proper and informed consultation to First Nations, they also jointly wrote and signed a Friendship Accord and had a traditional Wampum Belt made to signify the importance of their relationship. Each partnership I work with is unique with its own challenges, strengths, and potential; I support partnerships in defining their vision of success. My success is secondary and comes from the joy and pride I have in witnessing reconciliation.

Joelle: The biggest success for me is having the trust of clients to advance reconciliation through our legal system by taking on complex legal issues and seeking to have the court grapple with them through the lens of reconciliation, UNDRIP and DRIPA. This success though is really not mine but that of MT + Co as a whole which has always been committed to building a law firm where one of the primary pillars of our practice was the advancement of Indigenous interests at all levels.

4. How do you see reconciliation and decolonization being connected?

Asma-na-hi: I am not a fan of the terms, because the terms are colonial. To be in good relations is something that as a Nuu-chah-nulth womxn, I want to be in with others. To not be in good standing relations, when there were no “good” relations at the start, is not the term of reconciliation but conciliation. This is connected to an active response to creating a better world and life for Indigenous people. It is utilizing White Privilege (voice, access to funds, access to policies, etc.) to uphold a personal commitment in personal and professional life. However, the center of reconciliation and decolonization is still a colonial practice. Where it becomes cloudy is an act of expecting Indigenous leaders to lead the way. In my opinion, an honourable, humble process is to unlearn the colonial implications, relearn, and lead by example with humility to share the knowledge of reconciliation and decolonizing practices. At the same time, Indigenous people continue to be strong in cultural knowledge, practices, and language. Decolonization is something we all must learn but understand that Indigenous people are also dealing with multiple traumatic healing practices; all at once. Not to be maudlin or dismissive of the traumatic impacts on anyone, because it does take a community to heal a family. It does begin around everyone’s kitchen table, with difficult conversations and being humble to say, “I don’t know the answer, but let’s find out together.”

5. What advice do you have for Canadian organizations interested in starting their reconciliation journey?

Tanya: There is no template for reconciliation, each journey should be personalized and aligned to the values of the organization and their Indigenous stakeholders. Most organizations have identified their values, mission, vision…but how many have identified their Indigenous neighbours, stakeholders, or potential partners? Reconciliation isn’t one-sided. When one reconciles their bank account, both sides have to be equal. There are many ways to begin the journey, an initial step should include Indigenous engagement with the goal to build partnerships and identify win-win opportunities.

Zain: Pick up a map, look at where your organization resides, identify the closest Indigenous community from that point and get your people to visit them. We can visit many communities online, but it is more meaningful and valuable to go offline by making a personal connection, going to the ‘reserve’, talking to the real people, and understanding their history and culture, particularly including how and why reserves were allotted to them in the first place plus all the atrocities of the last few centuries. That would be a very good start to a lifelong journey of reconciliation that is very young as of today.

6. How do you spot “reconciliation washing” (much similar to “greenwashing”)? What advice do you have for people to avoid this pitfall?

Tanya: I think there are obvious signs of organizations just checking the box with no real meaning or commitment to change; strategies are created in silo with no Indigenous engagement, leadership has a ‘one and done’ attitude, and there are lack of win-win opportunities are present in their strategy.

Joelle: For me, reconciliation washing occurs where there is a performative recognition but no concrete action. An organization may provide all of their employees with branded orange shirts to wear on National Truth and Reconciliation Day, but the question is what have they done to assist with a deeper understanding of the historical background that got us here, to further the dialogue and understanding of reconciliation, to engage with Indigenous communities on whose land they operate?

7. What is one tool to adjust our mindset to align with reconciliation and away from the colonial, individualism mindset?

Tanya: If I was to apply the colonial way of thinking about tools to my traditional teachings, I would say that the tool would be incorporating Indigenous Frameworks within the way the organization operates, plans, and manages. By applying this tool, growth mindset will occur.

Asma-na-hi: Family. The one tool I have begun to ask people, as my ancestors would ask me while growing up: Where are you from? Who is your mom? Who is your dad? Who are your grandparents? This simple task to honour who you are and where you come from is a tool that aligns with reconciliation, in my opinion. It has been too often that people walk or be on a screen and begin talking business without introductions or who they are. The act of a Land acknowledgement must include who you are, where you come from, and what your intention is to continue to work, live, and learn on the traditional Lands wherever you are located. I have committed to offering my whole self. When I do a Land acknowledgement, I share my intention and share a story. I have been told my speeches are too long, and my response, I am not speaking just for myself but for my ancestors who were silenced for way too long. The act of reconciliation is not just a tokenistic or check box. It must be part of you and continue those conversations within your family. My hope, adults learn to be “whole” with each other, then the next generation will continue to be whole with each other. That is hope.

Joelle: Education.

8. How do we spot key indicators that signal we as a society are making progress on reconciliation in Canada?

Tanya: The main indicator would be that Indigenous people are equal. That our Indigenous Youth are graduating high school and post-secondary at the same rate as our non-Indigenous brother and sisters, that we are equal as homeowners, business owners, and beneficiaries of inter-generational wealth instead on inter-generational trauma and poverty. Stats show that suicide rates are 5-7 times higher amongst our Indigenous Youth and although graduation rates are on the rise, we still attend more funerals of our young instead of being invited to graduations, weddings, and family reunions. When Indigenous Youth are educated and employed, and thriving instead of surviving, then progress is being made.

Joelle: We have seen conversations around reconciliation and our colonial history moving to the forefront, a recognition of UNDRIP through statute at the provincial and federal level and an increased focus in our education system on Indigenous knowledge and perspective. These are all signs that we are engaged in moving forward but it is a long journey.

9. A question we sometimes hear in response to reconciliation is “what’s the end game? When do you know when reconciliation is completed?” How would you respond to this?

Tanya: This is a very colonial way of thinking and it sets up the organization for failure instead of change. When one changes their mindset to achieving equality by building partnerships with win-win opportunities, why would that partnership end? Reconciliation isn’t about reparations and punishment. Once Indigenous people, communities, organizations, and businesses are viewed as valued partners with strengths, rather than a burden, reconciliation can evolve and become something that the partnership defines together.

Asma-na-hi: What is the end game of reconciliation? This is a question I receive often. Is there an assessment or quality check to see “how well” Canadians are doing to support the idea of reconciliation and decolonization? Reconciliation grading systems is a colonial mindset. The government, organizations, and businesses may need a standard grading system to assess how well their governing bodies, organization, and systems are doing to create change for the better. My question is, what is the intention? Who is the grading system for? What is their end game? In my world, reconciliation and decolonization are not an end game but a way of life until Indigenous people’s lives are seen as equal and treated better than the past (yesterday), today, and the future (tomorrow). The day I start being seen as a respected Indigenous womxn when I walk into a mall, grocery store, bank, hospital, executive board room, conference, another country, a restaurant, and the list continues, will be a day when I think there has been a small baby step towards this idea of “conciliation.” A welcomed big step of courage is when someone else calls out the mistreatment and begin to protect Indigenous people’s human rights, including the strong relations to Mother Earth.

Zain: I cannot speak to what the end-game is but I can say that the journey of reconciliation is a lifelong one. It does not need to have an expiry date, but it certainly needs to be shared with every subsequent generation of people after us, so what happened in the past few centuries never happens again, in at least, Canada. Our collective knowledge, cultures, history, and development as people (Indigenous or non-Indigenous) need to be properly curated for the benefit of our future generations.